Argument, Fact, and Opinion: Using Student Misconceptions to Build Lessons

I try to avoid using the term "smart" in my classroom and for several reasons. First, calling someone "smart" leads them to believe it was something they were born with, something that just happened to them, and that they don't have to work for it. On the other hand, neglecting to use the term "smart"--especially if it is being used to describe behaviors such as giving a correct answer or performing a task correctly on the first try--makes children believe that there is something innate that isn't allowing them to be "smart." It defeats them, and it does so extremely unfairly. But there's one more reason why I don't like to use the word smart.

It's because many of my kids are "smarter" than me

Now, don't get me wrong, I'm not afraid of it. In fact, I welcome it, because what separates my students' and my ability to function in this classroom is not a matter of levels of intelligence; it's a matter of experience, it's a matter of the time they need and the time I have had to build my web, and I will always have that over them. Plus, I need some other "smart" people around. Otherwise, I'd be messing things up left and right.

Coming to terms with the fact that your children may be smarter than you isn't a terrible thing. In fact, isn't that what we want? Don't we want our children to grow up and be bigger and better versions of ourselves? Of course we do. That's what progress is all about. What's important to realize, and what most adults are afraid of, is that this realization minimizes nothing. I'm still the authority figure, and I still know more about the learning process; in fact, accepting that fact they are smarter than I am actually helps move our class along. They point out gaps in my logic and reveal places where I've explained something poorly, which only paves the way for richer and more rigorous learning for the entirety of my class.

And that's exactly what happened on Friday

One of my students was thoroughly confused by our TED Talks project.

"Wait, Mr. France, none of these are actually arguments," he said to me. "They're not stating opinions."

After about 20 minutes of trying to probe further, debate, rebut, and continue to explain how they are actually stating something debatable, my class's faces began to droop, and I could see that I was losing them. The entire conversation related back to a talk we watched by Edith Widder, who studied "The Weird, Wonderful World of Biolumiescence." In a way, this student was right, she wasn't arguing something right or wong per se. In fact, a lot of her talk came across in an expository manner. However, her claim, while vague and somewhat implied, was, in fact, there. Like I said, I was losing them; I had reached the point of no return for that day at least. Instead of dropping the topic and giving up, I told the kids that we'd begin the following week with a close analysis of Edith Widder's talk, looking for a claim, but I made some interesting changes while I was planning the lesson.

Using Sorting to Promote Critical Thinking

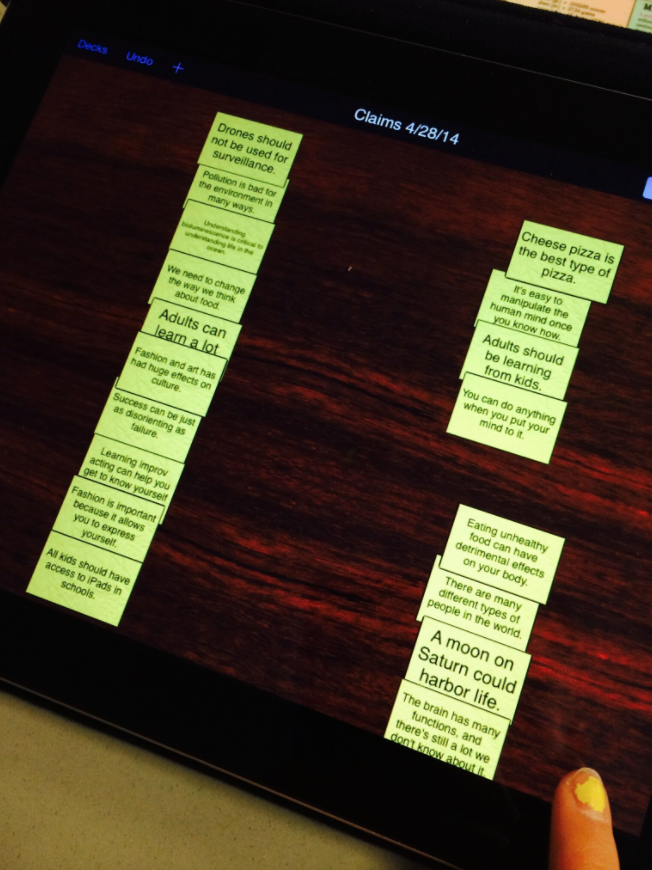

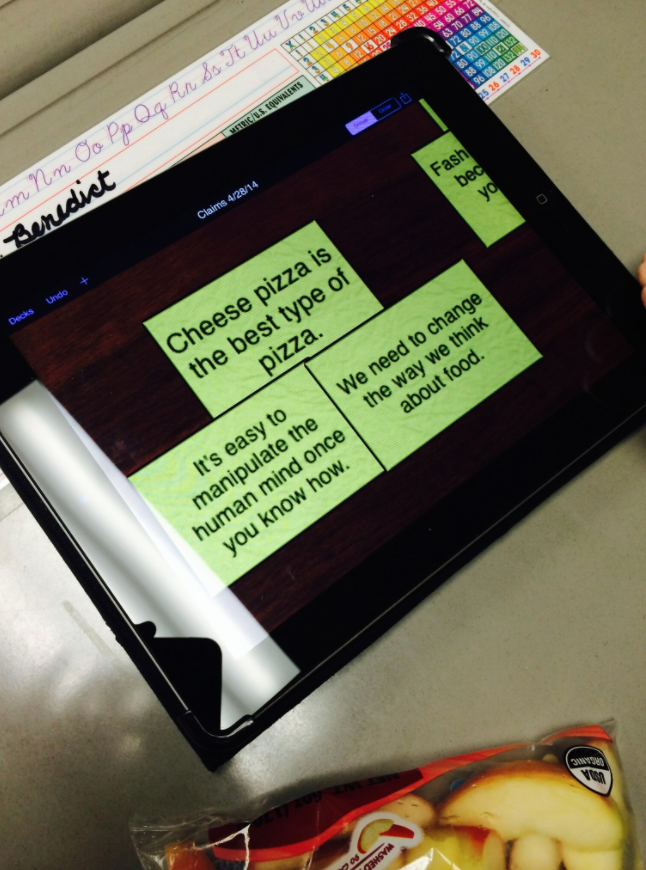

I noticed that this confusion related back to definitions and classifications, relatively low on the Bloom's scale, so I thought an activity centered around sorting in iCardSort would be a great way to engage thinking and get them talking about the difference between factual theses and argumentative claims. Although, as I was creating the sort, I began to realize that it wasn't all that clear. There was not really a fine line between each of these categories, and this came out in our discussions. Depending on background knowledge and student interpretation, the sentences were all grouped in a many different ways. Check out some student samples below. As you can see, we couldn't quite agree on what was fact, what was argument, and what was more of a subjective opinion. We had a great discussion about it, but the next part of the activity was where the real learning occurred.

The "Argument Continuum"

On my website, I had posted the following essential question for today's lesson: Where do we draw the line between argument, opinion, and fact? I used the engagement activity to help them see that these lines were not clear, making it hard for us to see how Edith Widder's (or many of the other talks) were argumentative pieces. So we watched her talk, and after our first discussion, some of the kids were able to pick out her vague claim. I still wasn't convinced they had a firm understanding, though.

In order to build upon the initial activity, I had the kids sort the cards differently this time. Instead, I asked them to create a continuum, going from the most subjective ideas all the way to the most objective facts, arranging the cards in one straight line. Of course, I reexplained the meaning of the two words, and let them start on their own. I even asked them to use a gradient of colors to show how it gradually moved from one end of the spectrum to the other.

From this task came a plethora of questions, leading to a great discussion around how scientific hunches eventually become theories, laws, and widely accepted scientific fact that can actually be observed, and how the context of time can have a great impact on what is considered to be a "fact," an "opinion," or what needs to be "argued" due to its level of controversy. Most importantly, from this task came the argument continuum, where we accepted the fact that the difference between fact, argument, and opinion isn't always clear, and that as long as we were using a variety of evidence to support our claims, that we would lie somewhere in the "argument sweet spot."

The Result

We decided that we wanted our TED talks to lie within the center of this continuum. We didn't want opinion pieces about favorite foods and preferences. Likewise, we wanted to avoid the objective end of the spectrum that only displayed or communicated facts and knowledge. Further, we decided that in order to give a TED talk, we didn't have to discuss something controversial or even something that his heavily debated, we simply had to make an argument, something that could be argued otherwise (even something as simple as importance or significance of a topic), in order to hold true to the mantra of TED, which is finding an idea worth spreading and communicating your passion for it.

Don't underestimate the power of kids. Take every opportunity you can to learn with them.